Taped Together: Creativity in Layers with Kirsten Hutsch

Kirsten Hutsch, a Dutch visual artist born in 1974 and based in Amsterdam, develops a body of work deeply rooted in the investigation of perception, reality, and representation.

Her artistic practice spans various media, exploring the ambiguity between the physical object and its image, between what is perceived and what is visually constructed.

Her approach challenges the traditional boundaries between painting and sculpture, revealing a continuous interest in material processes and gestures that carry meaning beyond technique.

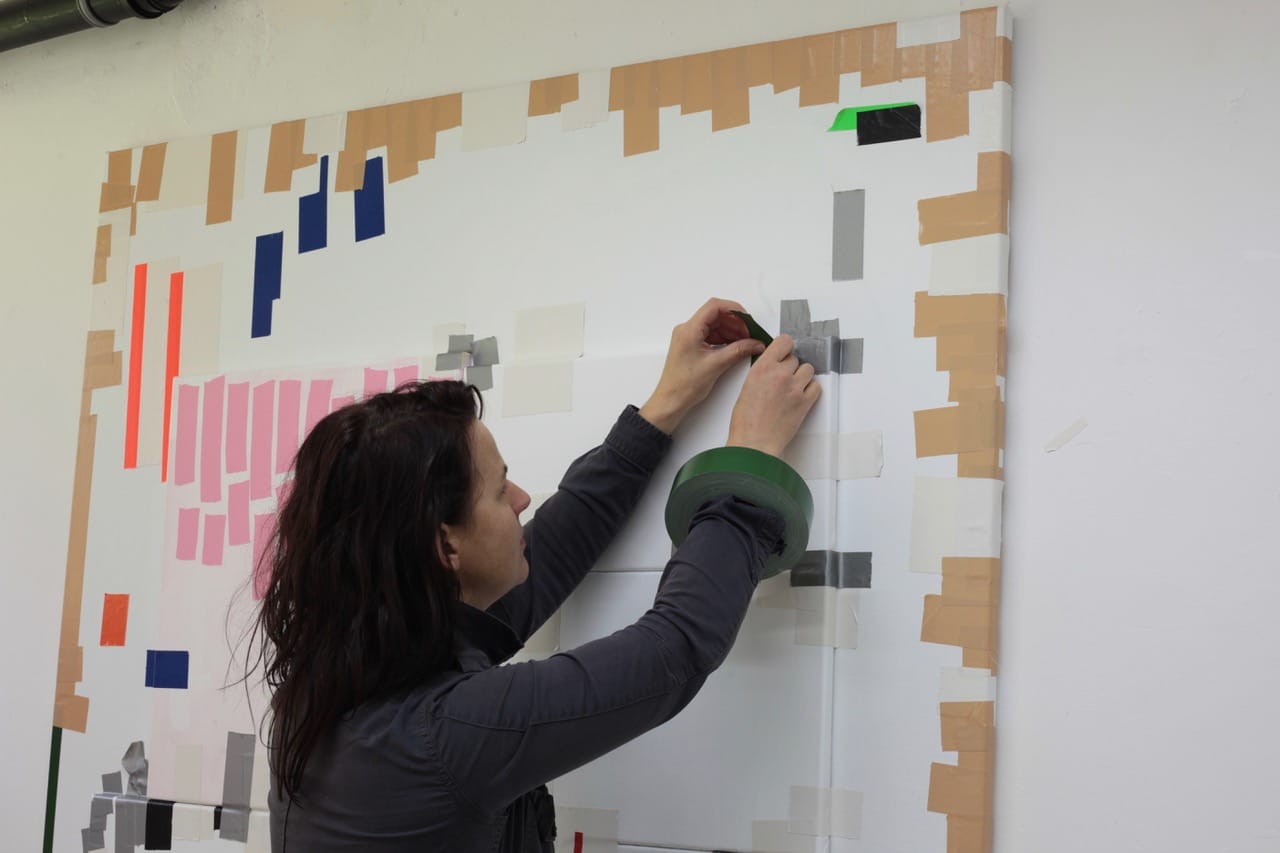

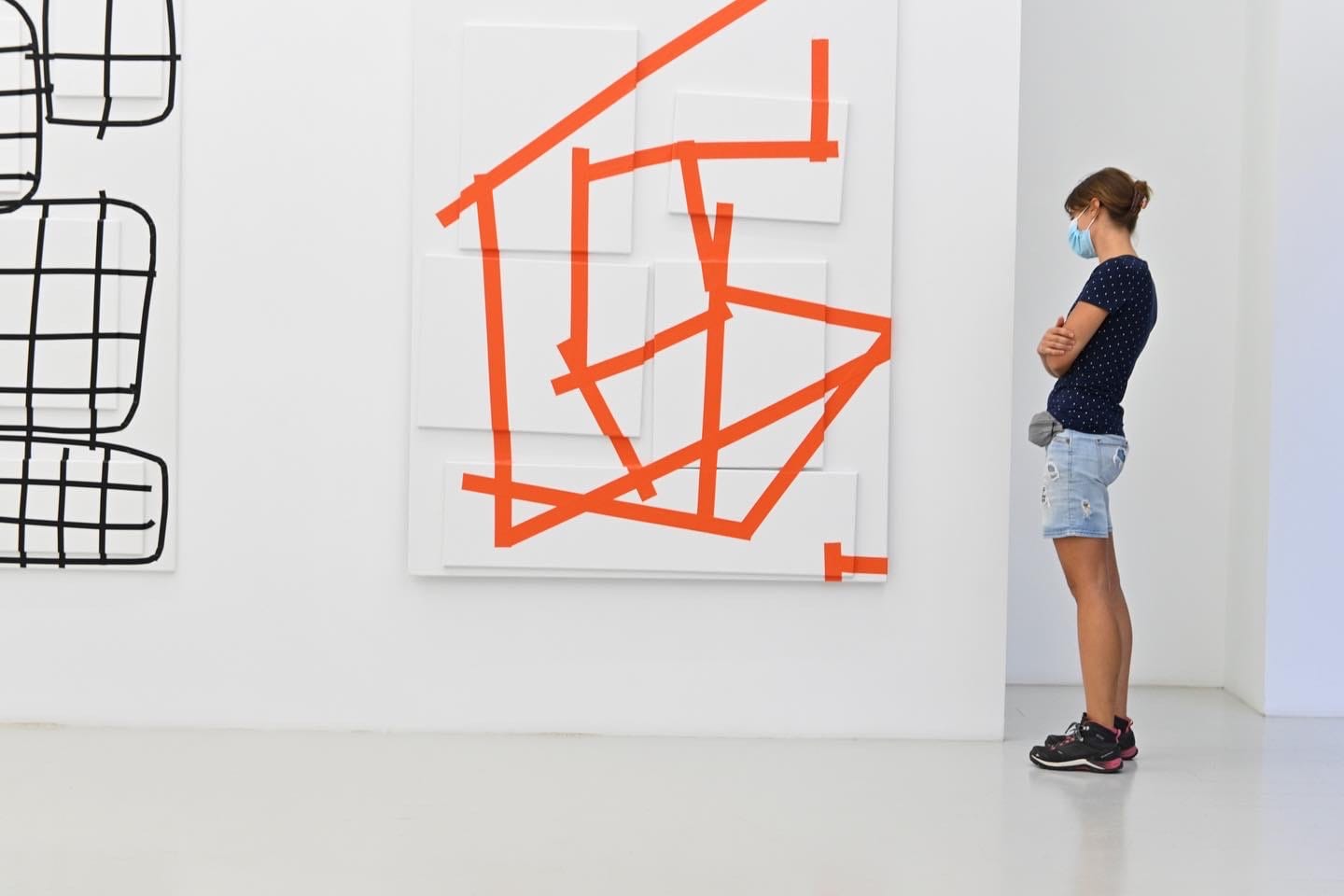

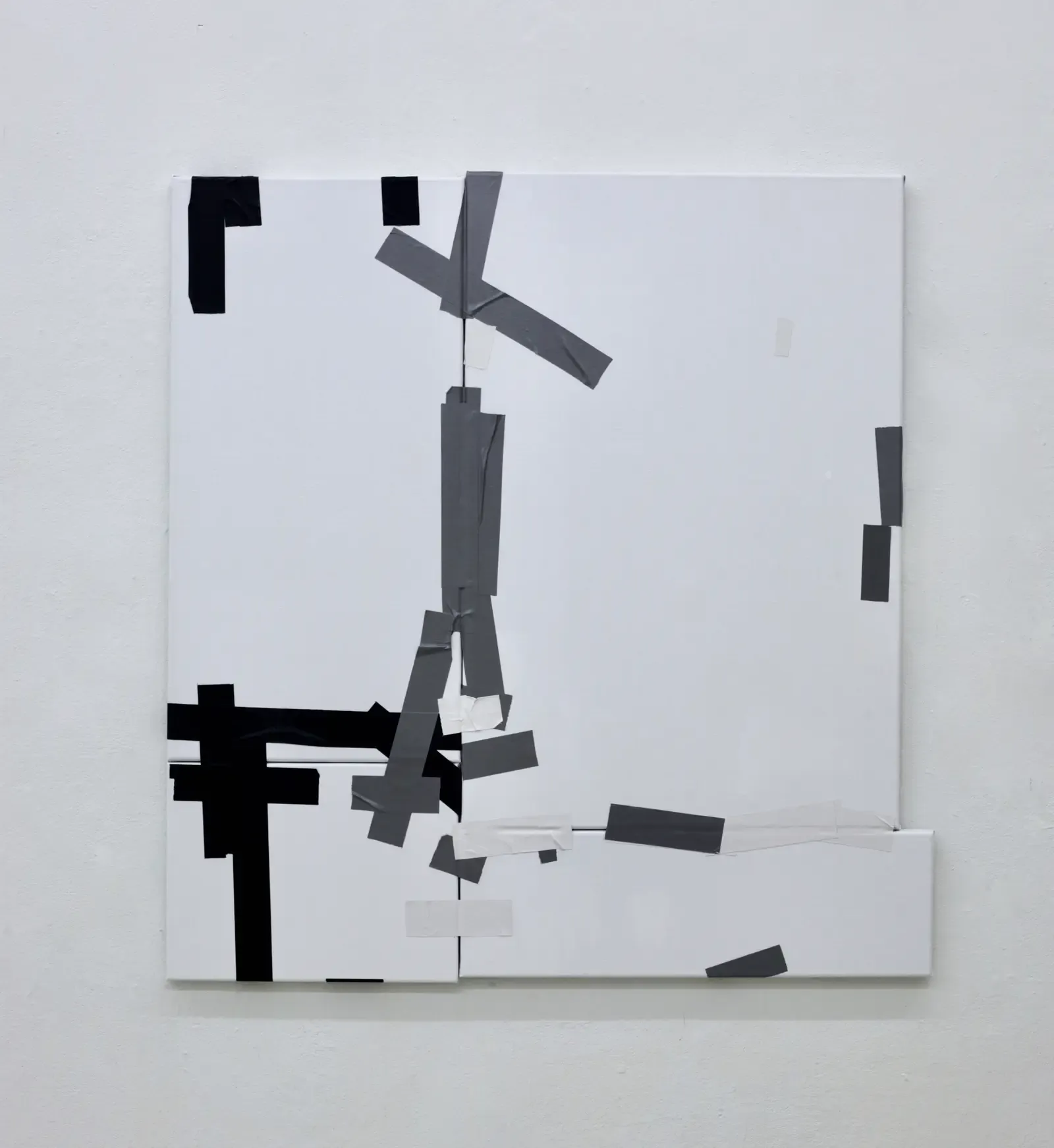

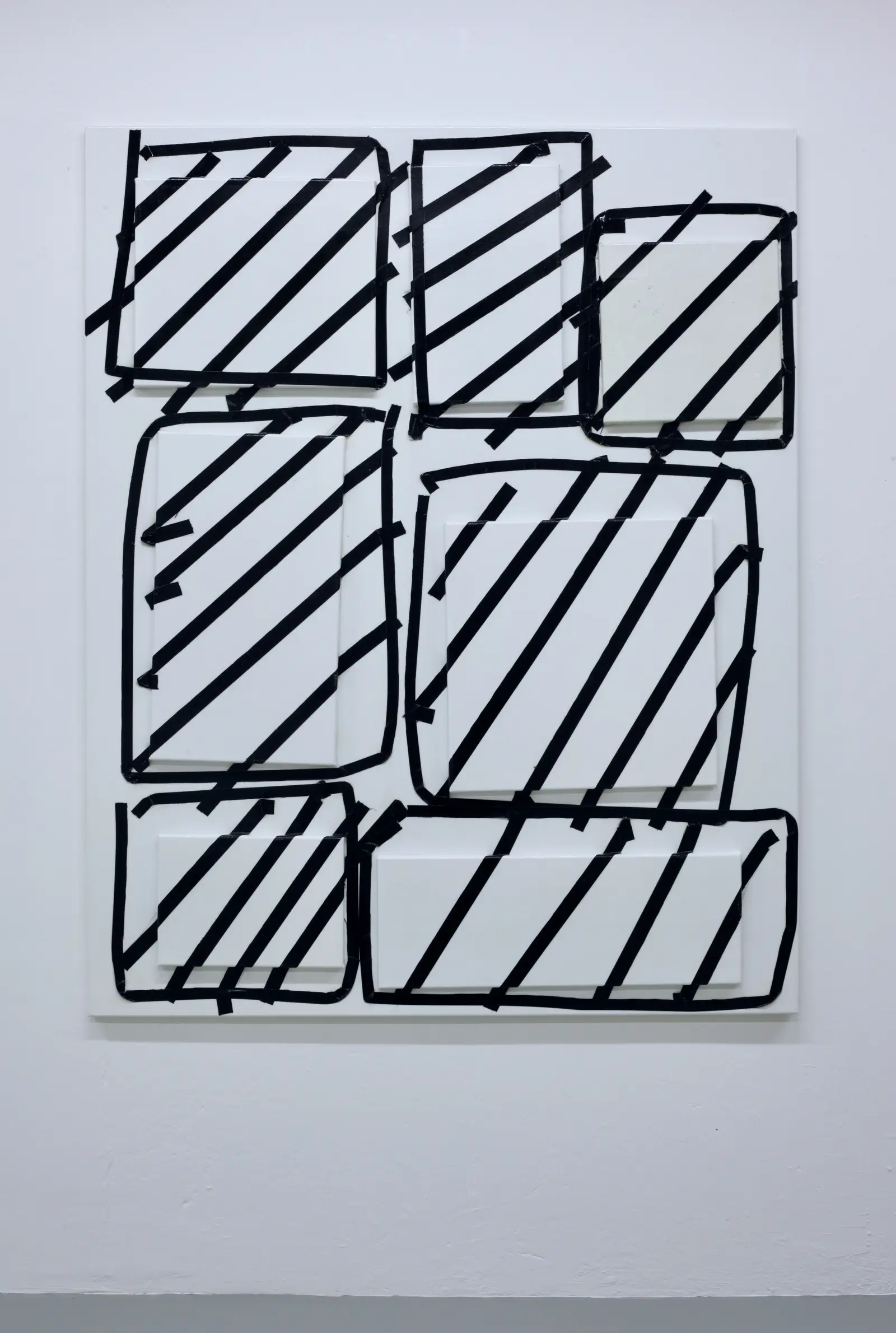

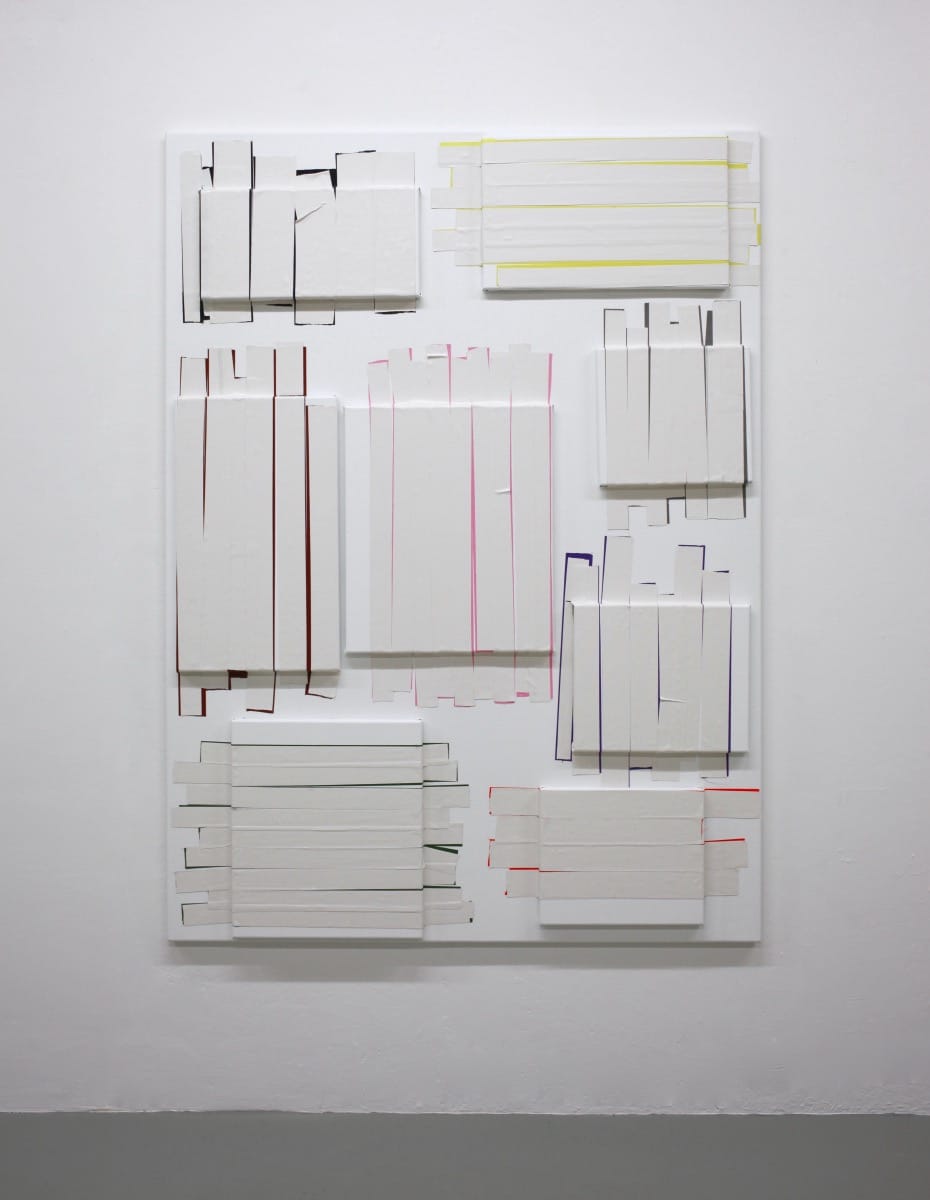

In series such as Taped Paintings, Hutsch uses adhesive tape not merely as a functional element, but as an integral part of the artwork, transforming what might be seen as temporary into a permanent structure.

The canvases—often multiple and juxtaposed—become plastic organisms in tension, where the supporting elements take an active role in the composition.

In another series, Domestic Series, the artist incorporates cleaning tools such as brooms and sponges into the act of painting, creating works marked by repetitive gestures that refer both to domestic routines and to artistic action itself.

This fusion between everyday life and creative practice points to a constant questioning of what constitutes a work of art and where it begins or ends.

Kirsten Hutsch’s work has been featured in various international exhibitions, where her research into presence, absence, and materiality is introduced with both sensitivity and rigor into the discourse of contemporary art.

Her work invites the viewer to reconsider how we see, touch, and understand the objects and images that surround us.

Interview between Kirsten Hutsch and DiFranco:

1. How do you usually start your day in the studio? Do you have any rituals or habits that help you connect to your creative process?

Not really — in the studio I usually just pick up where I left off the day before.

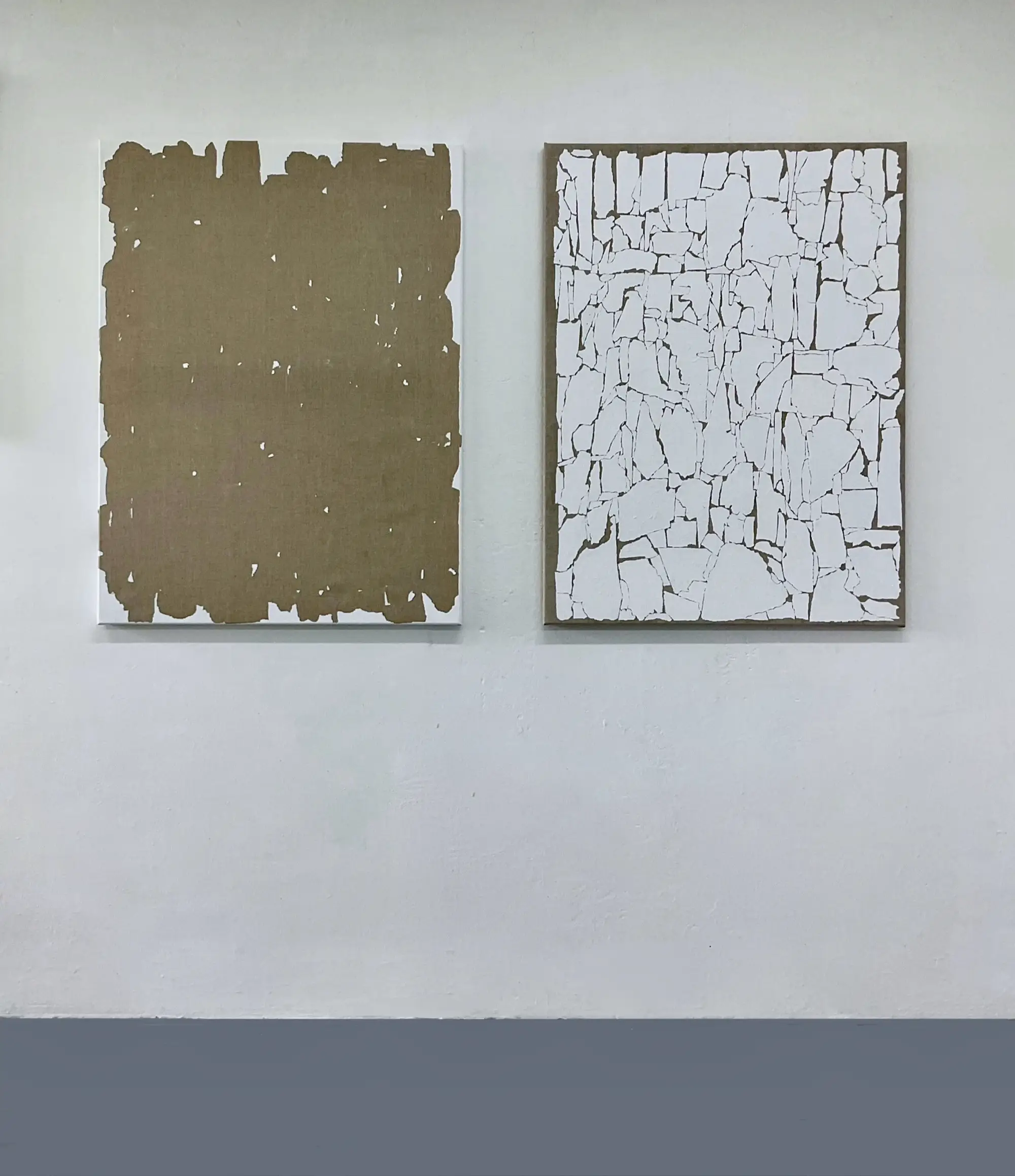

Left image → Untitled, 2025 by Kirsten Hutsch – Acrylic, artist-made gaffa tape, impasto gel on linen, 95 × 142 cm. Right image → Hulk, 2020 by Kirsten Hutsch – Artist-made gaffa tape, hockey tape, impasto gel, and UV varnish on linen, 150 × 110 cm. All rights by the Artist

I do practice Transcendental Meditation, twice a day for 20 minutes: once before I head to the studio, and once around four o’clock, in the studio. That helps me stay centred and present throughout the day.

2. What led you to choose unconventional materials like adhesive tape as a central element in the Taped Paintings series?

Tape allows me to reinvestigate painting without being a painter. In these works, tape is a reference to paint and abstract image.

Where paint has this morphic, vaporous quality, tape is non-illusionistic: it is what it is, it retains its ‘objecthood’. Tape creates an image that foremost represents the method of its application.

Kirsten Hutsch - Artnueve

Therefore the Taped Paintings remain in this ambiguous state, in which artistic gestures intersect with pragmatic actions - sticking individual canvases together.

Due to the tape’s adhesive quality - it can be replaced again and again – therefore the paintingholds a potential to continue the process of decision-making.

As opposed to paint, replacing the tape leaves no trace: replacing it removes the previous action. As a result, the process is not visible. This renders the work a directness. It stays fresh and crisp, like the first mark.

There is no residue of last week’s work, it stays in a state of endless beginning an simultaneously one of endless possibilities.

Even when ready, after I seal and fix the tape, the intellectual idea that it is peelable remains: the work can still be reconstructed in one’s mind.

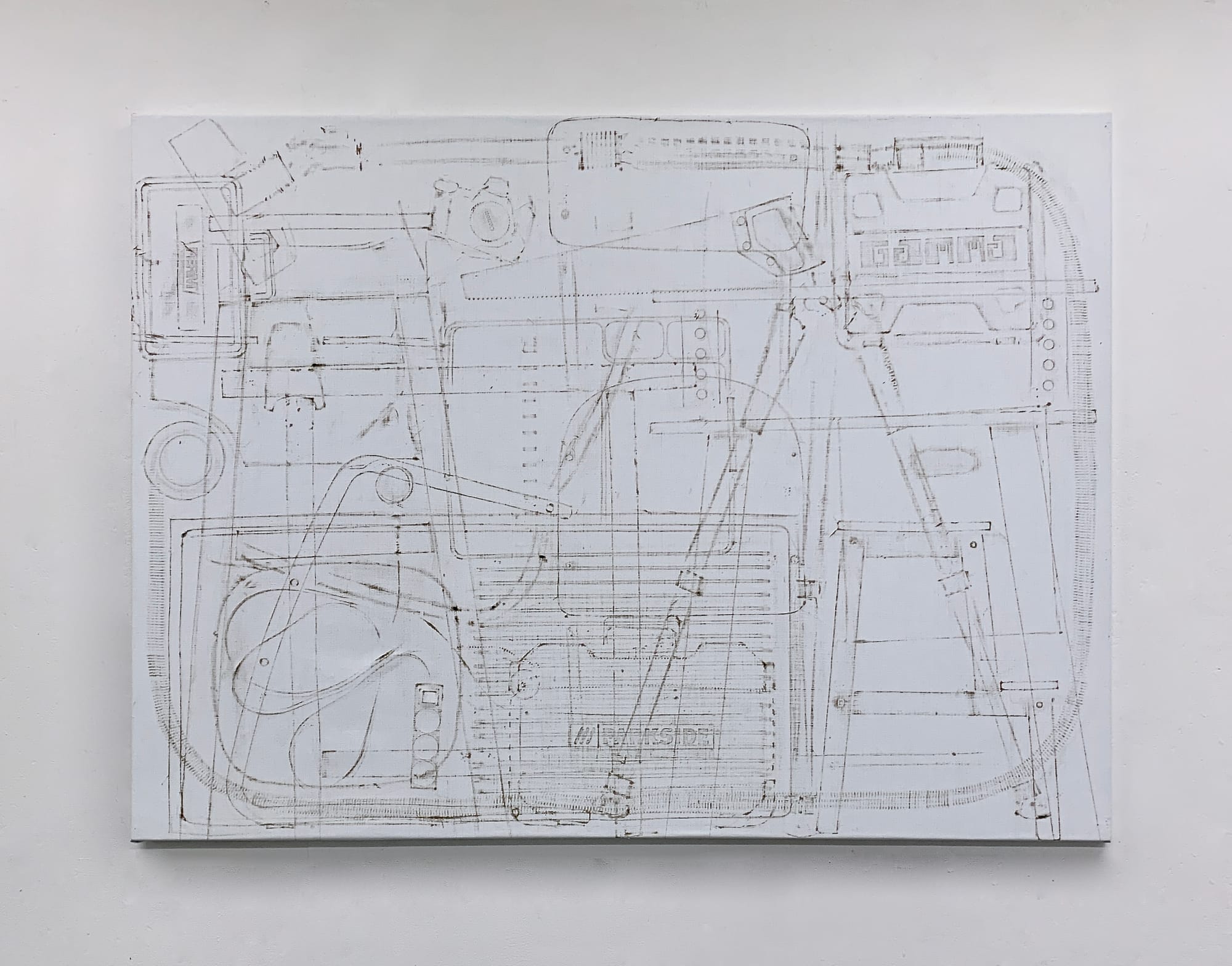

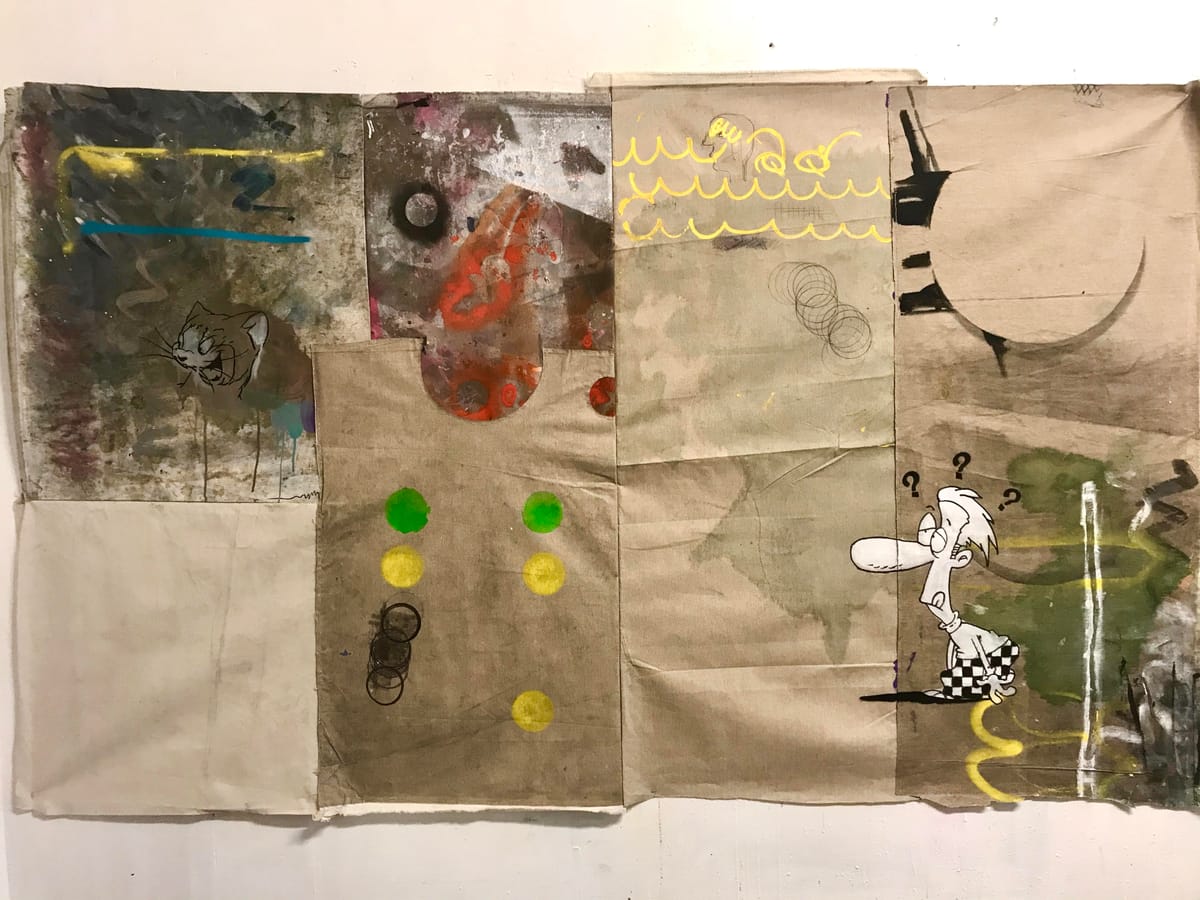

3. Where do the objects used in your ‘Inventory Paintings’ come from—are they found, from a personal archive, or are they created specifically for the work?

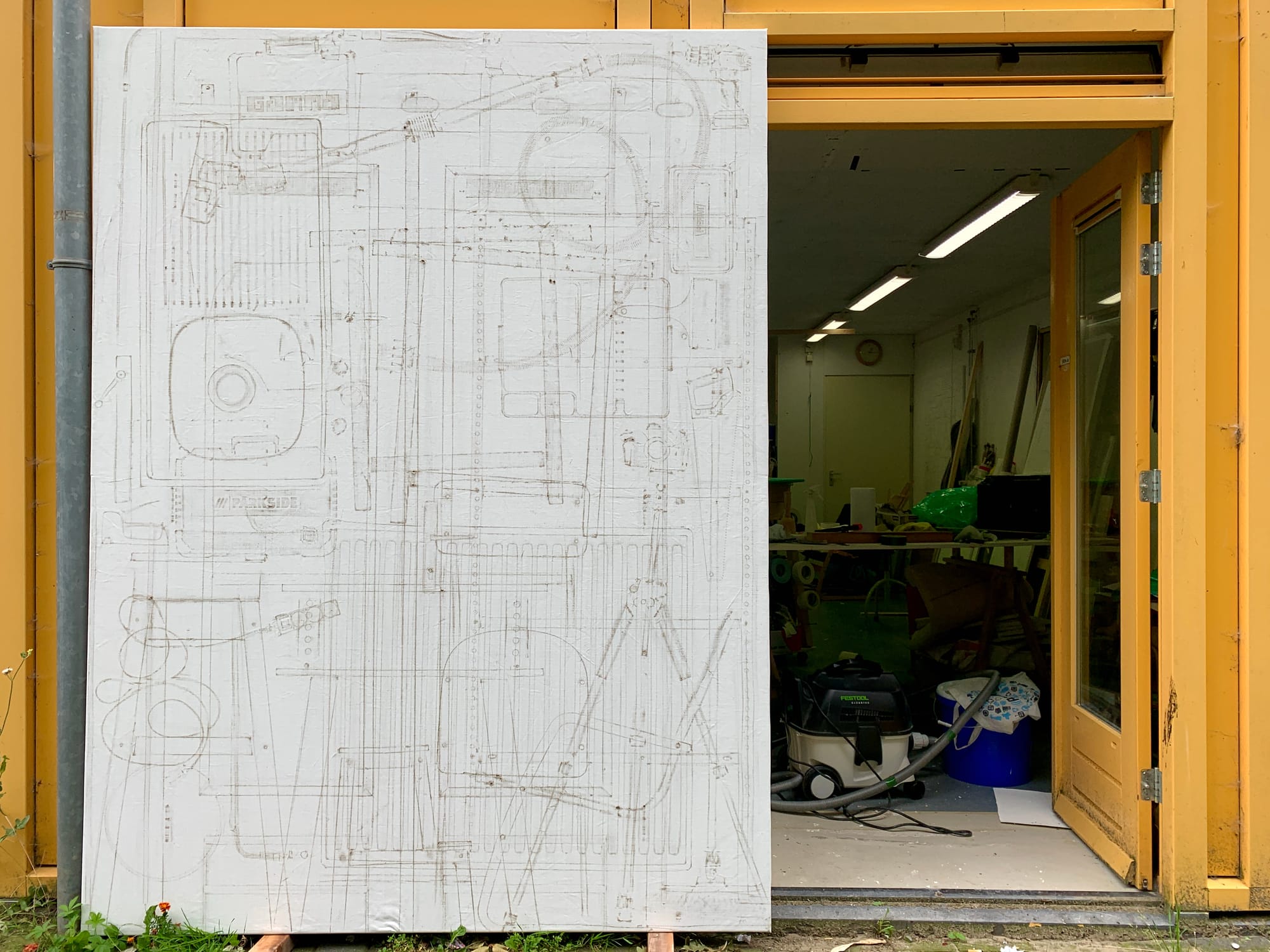

They are objects from the studio itself — furniture, tools, and architectural elements like the sink, window, or door.

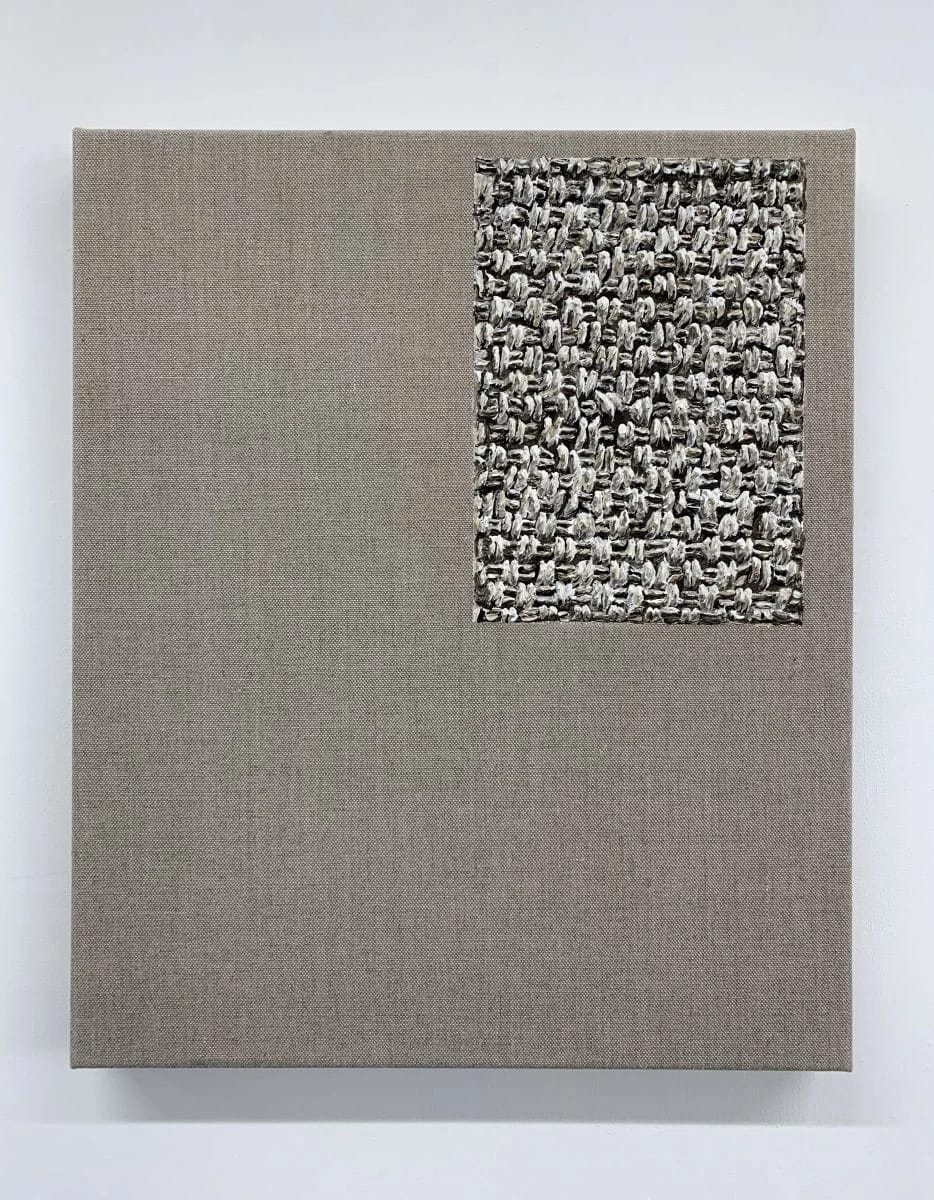

Left image → Kirsten Hutsch, Untitled (Bleu), 2023, 140 × 180 cm – Acrylic paint, artist-made gaffa tape, hockey tape, impasto gel, and UV varnish on linen. Photo: Sander Tiedema Right image → Kirsten Hutsch, Taped Painting No. 20, 2023, 111.5 × 105.5 cm – Artist-made gaffa tape, impasto gel, and UV varnish on linen. All rights by the Artist

The series began during a residency in Berlin, where I wanted to document the studio space by using frottage: placing objects under primed linen and abrading the gesso surface with sandpaper to reveal their contours.

NL=US Art Rotterdam - “When You See me the I is Gone” solo exhibition by artist Kirsten Hutsch

The resulting images are both direct imprints of reality and ghost-like traces — a kind of mechanical archive that reflects on presence, memory, and perception.

4. Do you see the act of taping and mending as a metaphor for emotional or social processes?

No, not directly. For me, taping is more about material investigation and the logic of construction than symbolic or emotional repair.

Any metaphorical associations are secondary and not the starting point of the work.

5. How do error, improvisation, and imperfection become central elements in your visual language?

They are embedded in the process—they are one with it. I don't separate them as distinct elements; instead, they arise naturally through the way I work.

6. Which artists, movements, or references do you feel resonate with your practice—either consciously or unconsciously?

My work shares a kinship with artists and movements that question the boundaries between material and meaning, perception and reality.

Like the Japanese Mono-ha artists, I explore the tension between things as they are and the meanings we impose on them—working not to transform materials, but to situate them in a way that makes their presence and relationships perceptible.

The Korean Dansaekhwa movement resonates in its procedural rigor and the merging of gesture with surface, where the act of making becomes indistinguishable from the image itself.

In a more conceptual register, my work aligns with Joseph Kosuth’s investigations into the construction of meaning—shifting attention from what a work depicts to the logic of its framing and the conditions of perception.

In a similar spirit, Arte Povera resonates through its use of humble materials and its resistance to institutional frameworks—emphasizing the open-ended, processual nature of meaning-making and the poetic potential of matter itself.

The American Minimalists, too, rejected narrative and illusionism, favoring direct physical encounters with materials and spatial context. I’m drawn to artists such as Sol LeWitt, Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman, and Carl Andre.

While these historical movements and artists resonate with aspects of my practice—through their emphasis on material, process, or self-reference—my work extends these concerns into a contemporary context.

It reflects a heightened awareness of the viewer’s role in meaning-making, and aims to hold open the space before interpretation solidifies.

Rather than arriving at a definitive image or reading, the work seeks to suspend perception—inviting a kind of quiet attention in which the image is not something to be decoded, but something to be encountered.

7. What is it like to be a woman artist in the contemporary European art scene? Do you feel there are barriers or changes underway in the art world?

I went to art school in the early 1990s, at a time when women artists were significantly less visible. Back then, it seemed that only women of exceptional calibre gained exposure, while male artists of more average quality had easier access to the art world.

Since then, the numbers have become more balanced, and I have really enjoyed seeing the rising appreciation for older female artists like Phyllida Barlow and Rose Wylie.

In recent years, there has been a strong focus on inclusion, representation, and social justice — often as a necessary response to centuries of exclusion in art history. Personally, I have never strongly identified with gender; I have always considered myself simply an artist.

8. The Taped Paintings series explores themes of fragility and resistance. How do these ideas relate to the world we live in today?

These works don't comment on current events or surface-level social dramas. Rather, they seek to touch something more metaphysical: a deeper stratum of existence beneath the noise of the day.

Fragility and resistance here are not political stances, but ontological conditions—reflecting the paradox of being both contingent and enduring.

9. Do you see art as a space for political critique or social transformation? Does your work engage with that space?

Art is certainly a space for political critique and social transformation—but not all art has to function in that way.

My work doesn’t engage directly with political discourse, but perhaps it does so indirectly, by proposing a different mode of attention.

In a world saturated with immediacy and opinion, I try to create spaces where perception slows down—where meaning isn’t delivered, but unfolds.

In that sense, the work may resist dominant forms of communication, and that resistance is, in itself, a quiet form of critique.

11. What advice would you give to emerging artists trying to find their voice amid the pressures of the current art system?

A. Never lose sight of why you became an artist in the first place — which, for most of us, had nothing to do with the art establishment.

B. Stick to your guns. Don’t make art just to fit in (see A).

C. Understand the concepts behind your work and find words to articulate them

D. Engage, get out there. See shows, apply for residencies, connect with others — and don’t wait for permission: initiate your own exhibitions and collaborations with peers.

12. As your work evolves from one series to another, what is the conceptual or theoretical thread that connects your overall practice?

In recent years, I have deliberately chosen ontological research into the nature of being as the core of my practice.

I investigate the ambiguity between the essential reality of the physical object and the inherently artificial nature of its presentation as an image. This tension is central to all my work, regardless of the materials or forms I use.

What connects my work across all series is a persistent attempt to stretch the moment before interpretation — to create a space where the image or object does not point to something else or tell a story, but simply is.

I focus on that fleeting moment in which meaning is not fixed, but open, ambiguous, and in flux. This invites the viewer into an encounter with the work itself, rather than with a predefined message or narrative.

13. How do you view today’s art markets—especially regarding the appreciation of experimental processes and alternative materials?

What I notice in today’s art world — especially in the institutional and market-driven sectors — is a tension that feels strangely familiar in historical terms. It reminds me of the Baroque response to Mannerism.

In Mannerism, we saw a shift away from Renaissance ideals of balance and harmony towards a more personal, stylised, and often ambiguous visual language.

Artists began exploring what art itself could do — a kind of early autonomy of the medium. The Baroque that followed was a correction: art became emotionally persuasive, narrative-driven, and aligned with religious and political authority.

Looking at the present moment, I sense we’re once again in a corrective phase.

After decades of prioritising individual expression, ambiguity, and autonomy — especially within postmodern practices — the emphasis has shifted towards collective narratives, inclusion, representation, and social justice. This is important and long overdue in many respects: voices that were historically excluded are finally gaining space.

But I also see a paradox. There’s greater visibility, yes — but often within predefined themes. Freedom is offered, but within a narrow thematic scope. For some, this is liberating. For others, especially those working with more ambiguous, introspective, or materially experimental approaches, it can feel limiting.

So while experimental processes and alternative materials are still valued, they’re often appreciated most when they align with current ideological frameworks.

It raises a deeper question: is art today still a space for radical individual inquiry, or is it becoming another instrument of collective morality?

14. Your work has spanned different supports and formal explorations. Is there an idea or why that remains constant despite these changes?

Yes. Despite the shifts in materials, supports, and formal strategies, the underlying idea remains constant: I explore a new kind of materialism that embraces the ambiguity inherent in reality, material presence, and sensory perception.

Kirsten Hutsch - Gallery Viewer

Rather than treating art-objects as passive carriers of external meanings, I approach them as independent agents with their own presence and status.

Interview by DiFranco

Follow Kirsten Hutsch on Instagram.

This is independent art writing - no paywall, no ads, no bullshit.

If you value this voice, support it.

Di Franco on Munchies Art Club

Related artists:

Member discussion